From time to time, new tools emerge that make it significantly easier to examine older malware. In 2017, Symantec’s threat intelligence team published research regarding the Dragonfly group, an adversary with an apparent interest in performing reconnaissance against energy sector companies. One of the reported malware families, “Backdoor.Goodor,” is written in Golang and the blog post states that it “provides the attackers with remote access to the victim’s machine.”

In recent years, several free options have become available to help reverse engineer these types of Golang binaries, replacing premium (but extremely well documented) methods and making this type of analysis particularly more accessible.

This post walks through the reverse engineering of a Goodor file, examining its capabilities and discussing key principles of these types of files.

Key Concepts

This blog notes that there are a few key concepts relevant to understanding Golang binaries:

– When first disassembled, Golang binaries will have a nearly unreadable number of unlabeled functions

– Golang binaries contain a section referred to as “gopclntab” that stores function information.

– For Linux/Unix binaries, this is an actual named section. For Windows binaries, it is not.

– This section has the same “magic bytes” in both types of binaries and follows a uniform structure.

In particular, this blog recommends that those interested in a deeper understand of the subject start by watching Joakim Kennedy’s two presentations which provide significant detail regarding the structure of Golang binaries. Mr. Kennedy’s tool, Redress, is a key part of current Golang reverse engineering and is used in this analysis.

Finally, this analysis uses Cutter, a GUI-based implementation of the Radare2 framework. When a Golang Linux binary is opened in Radare2 or Cutter, both tools automatically identify the gopclntab section, parse function names from this section, and relabel the assembly as needed. However, this blog noted that they did not behave this way for Windows binaries, where this section is not explicitly created. Redress provides a workaround for this issue.

This post relies on a Linux VM for Cutter, Radare2, and Redress, as the Windows version of Cutter didn’t allow for the execution of Redress in the command line and the Windows version of Radare2 functioned poorly with #!pipe commands. The debugging itself takes place in a Windows VM.

Technical Analysis – Initial File

File: ntdll_installer.exe

MD5: f2edff3d0e5a909c8d05b04905642105

SHA1: c8c8329449c18445330903dd6a59d0b4098d9670

SHA256: 5a7ace894461c2432fe9b52254cbc5c3f5bbce0c91a416154511a554dba6f913

This blog revisits an older malware family with newer tools to obtain a better understanding of the file. One place to start is Symantec’s original write-up, which stated:

1. “Backdoor.Goodor… opens a backdoor on the compromised computer”

2. “When the Trojan is executed, it copies itself to the following location…”

3. It “creates the following registry entry…”

%AppData%\NT\ntdll.exe ddd-073d7bac5d624bb40adbb25f55eb693d

This blog notes that the current Google-indexed page for this malware leads to a Broadcom page that states, “You have arrived at this page either because you have been alerted by your Symantec product about a risk, or you are concerned that your computer has been affected by a risk.” As neither statement is true, this blog has linked to the archived version instead.

As this analysis will show, Symantec’s write-up is a close approximation that’s not quite forensically accurate. The “copied” file is actually a dropped embedded file, and the registry entry changes slightly from device to device.

Identify Function Names

The first step for this analysis is to use the Redress tool with the -src switch to identify function names. When run against this file, the tool produces the following output:

Package main: C:\Users\User\go\src\i

File: i_main.go

main Lines: 15 to 19 (4)

TryDoMain Lines: 19 to 29 (10)

TryDoMainfunc1 Lines: 20 to 24 (4)

DoMain Lines: 29 to 61 (32)

GetFn Lines: 61 to 76 (15)

CreateBat Lines: 76 to 110 (34)

StartA Lines: 110 to 113 (3)

File: r.go.template.impl.go

init Lines: 6 to 6 (0)

Package e: C:\Users\User\go\src\e

File: e.go

Decode Lines: 53 to 93 (40)

Decodefunc1 Lines: 70 to 155 (85)

FromB64 Lines: 93 to 121 (28)

Decrypt Lines: 121 to 144 (23)

HashStr Lines: 144 to 150 (6)

RandomHashString Lines: 150 to 153 (3)

init Lines: 155 to 155 (0)

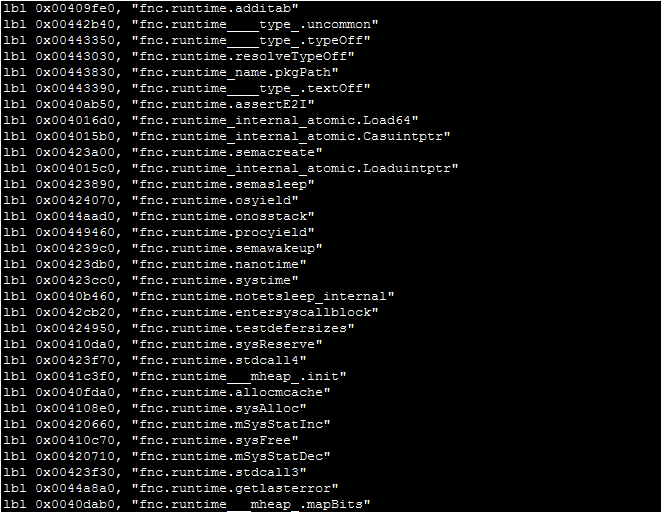

This output represents the author-added functions to a Golang binary. Golang binaries are large as they also incorporate dozens (or hundreds) of additional library functions, and so this output separates the most important sections.

The output also provides some hints: we can postulate that the malware likely performs some sort of Base64 decoding and decryption (FromB64, Decode, Decrypt) and may also create a .bat file (CreateBat). Notably, we don’t see anything indicative of command-and-control (C2) traffic.

Create a Function Map

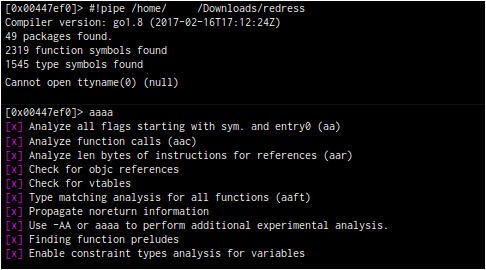

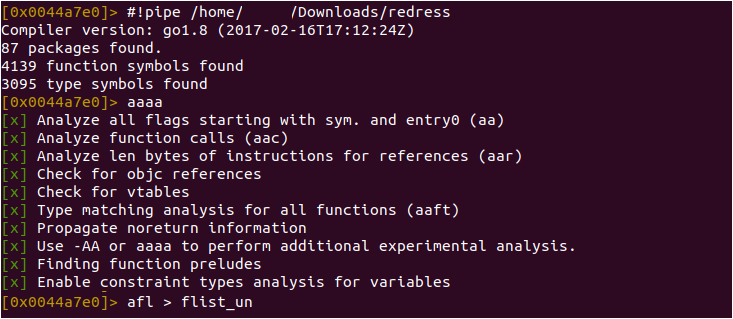

With the primary functions identified, we can map them out. Open the binary in Cutter with the slider for analysis all the way to the left, indicating no analysis. Using #!pipe, run the Redress tool. Finally, run “aaaa” to perform analysis and go to View-> Refresh Contents.

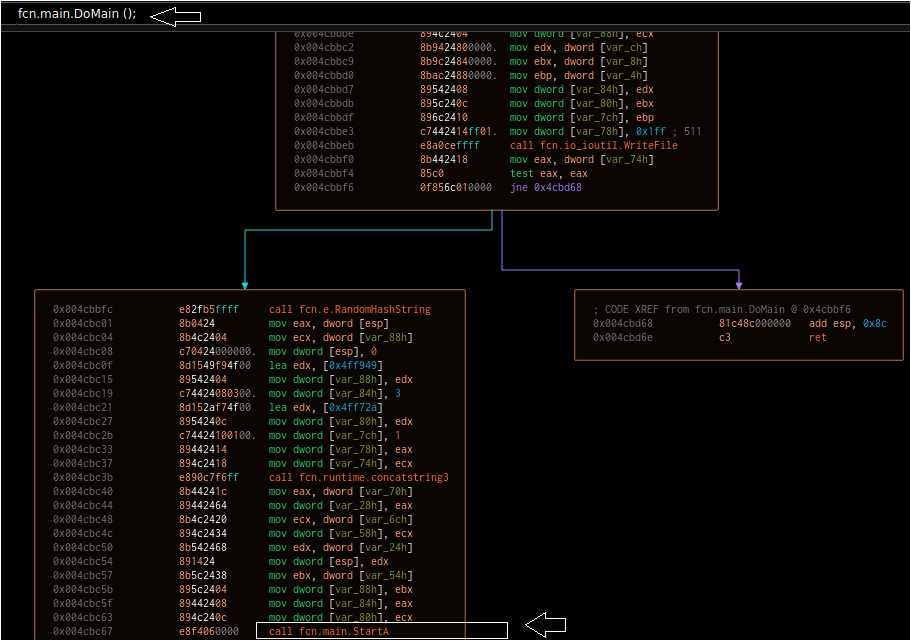

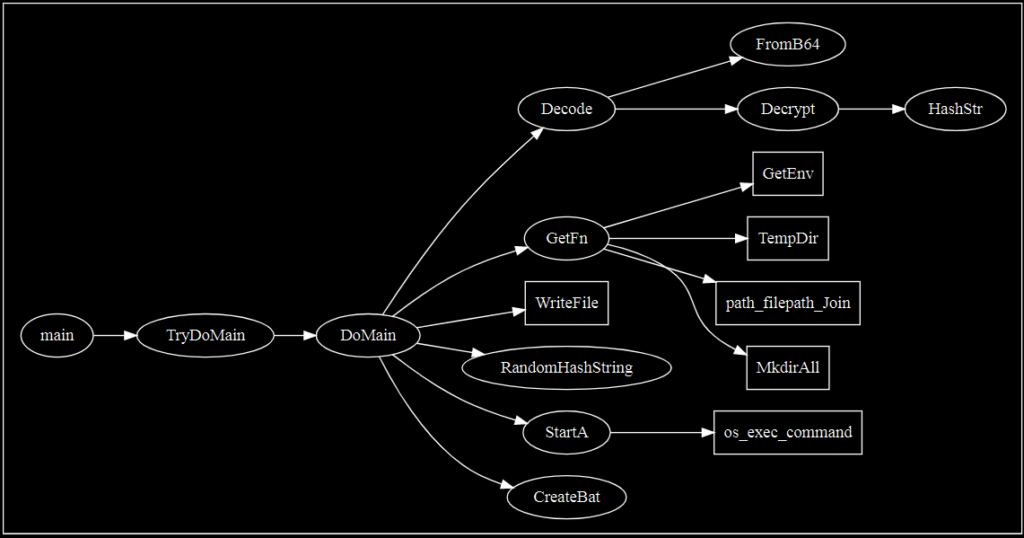

With the function names populated, we can begin mapping out a smaller call-tree. As with other disassemblers, we can select each function name in graph mode or use the cross-referencing features to identify function relationships. For example, DoMain makes several additional calls in the following order:

– Decode

– GetFn

– RandomHashString

– StartA

– CreateBat

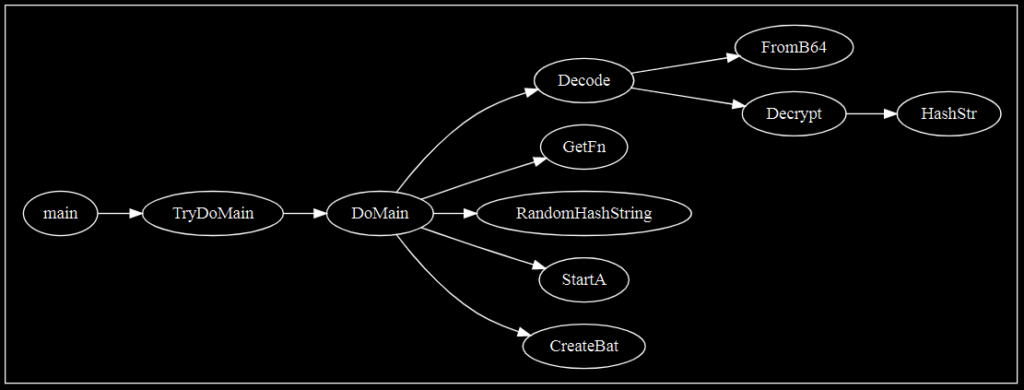

Decode, in turn, calls “FromB64” and “Decrypt.” Using this information, we can construct a simple call map.

This particular sample only uses each of these functions one time, providing an easy-to-understand workflow. This is of course not necessarily typical for all malware. The graph above may also be too simple, as it omits several important native Golang calls that could provide a broader understanding of some of these functions.

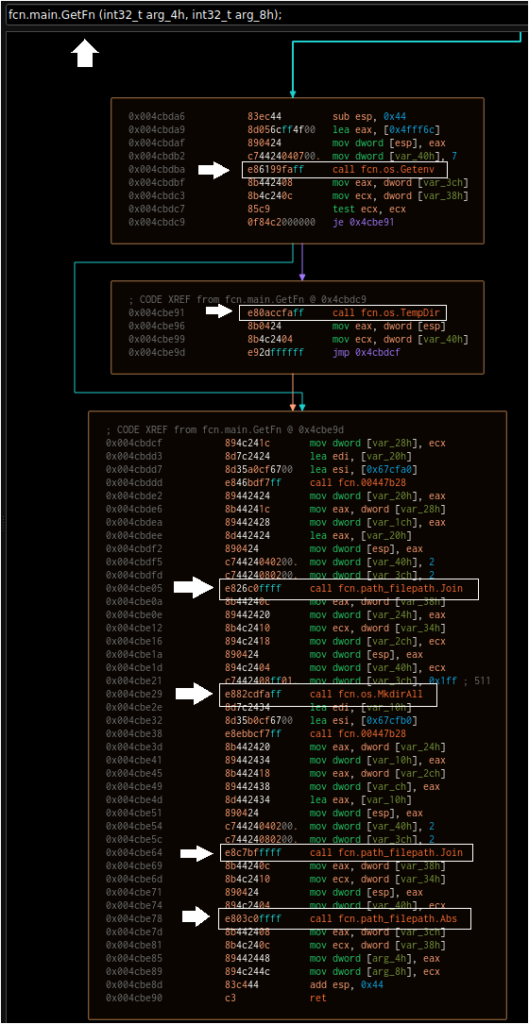

Consider the GetFN function: within this function are calls such as “GetEnv,” “TempDir,” and “MkdirAll” that strongly suggest that a file and/or folder is being written to a specific path. Without this information, one might have assumed “GetFN” was simply obtaining the name of a file (or the file running). With that in mind, we can create a more complete graph, with boxes differentiating the native calls.

With these functions mapped out, we can hypothesize a workflow such as:

1. The malware Base64 decodes and then decrypts something.

2. The malware creates a filename and/or directory somewhere, possibly in the Temp directory.

3. The malware writes something to the disk.

4. The malware calls StartA, which executes something.

5. The malware creates and runs a .bat file.

It’s time to begin debugging to test these hypotheses.

Debugging

I prefer the x96 suite for debugging. The most important thing to do before actually running the debugger is to rename the key functions we’ve identified. These include the author-added Golang functions plus any other interesting ones, such as those within the GetFN call. There are a few options here; in this case, I opted to do this manually, but you can also use Radare/Cutter + Redress + the “aaaa” and “afl” commands to get an address-function pair list (copying it to a file), and then create a comment or label script for x96dbg. For a larger file, that might be the most practical approach.

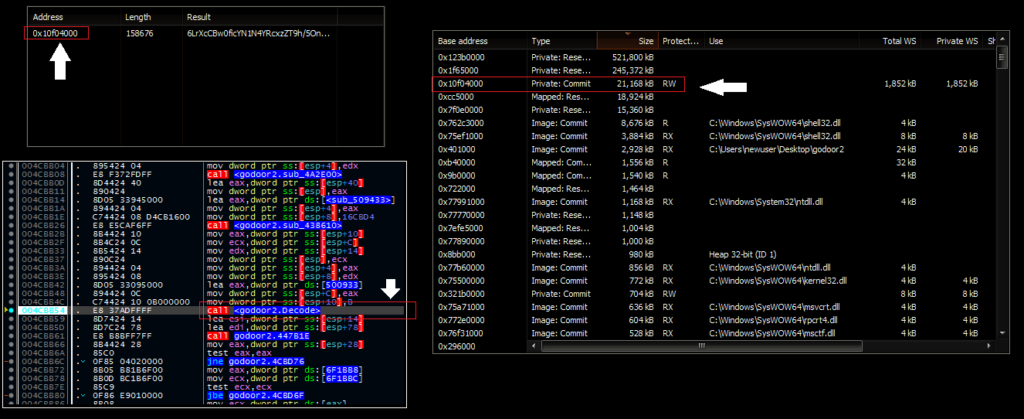

The first order of business is to examine the decoding hypothesis. The malware contains a large block of Base64-encoded data, visible in the strings via Process Hacker. As the string is several thousand characters long, it is easy to stop in a single memory section. After stepping over the Decode function (which in turn triggers the FromB64 and Decrypt calls), this section will populate with the decoded and then decrypted data:

Next, is the GetFN function call. Earlier, we hypothesized that this should create a file path or directory in the user’s Temp folder. Stepping through this function, we can see it creates a directory at AppData\Roaming\NT\

The malware will also create a filename, ntdll.exe, and append it to this path. When the function exits, it uses the WriteFile call to write the decoded executable to this location. The StartA function then issues a system command to run this. For the purposes of this analysis, I copied the executable to the desktop and replaced it with a renamed FakeNet Mini executable to examine the CreateBat function.

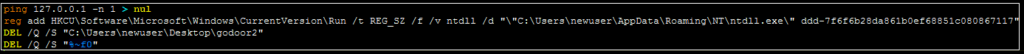

From a static perspective, CreateBat demonstrates a string load. The program identifies the address and length (in this case, 25 characters) of a string containing a ping command. The rest of the function also performs a string replacement for a registry key value to be added. The end result is a .bat file written to disk:

This file creates an HKCU runkey that will cause the dropped payload to execute any time the user logs in. It will also silently delete the initial dropper and delete itself. Following the execution of this batch file, the program terminates itself. At this point, we can look at the dropped payload.

Technical Analysis – Dropped Payload

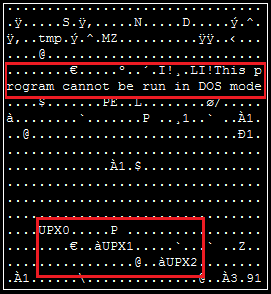

The dropped payload is a UPX-packed Windows executable.

Filename: ntdll.exe

MD5 (packed): 8943E71A8C73B5E343AA9D2E19002373

MD5 (unpacked): ca818c14f69bef7695c0e2ff127e6d9b

SHA1 (unpacked): 115d12e0fb73445a788ebe7bdf3cab552b3cb9af

SHA256 (unpacked): b5278301da06450fe4442a25dda2d83d21485be63598642573f59c59e980ad46

Following the same steps as above, we can identify the author-created functions.

Package e: C:\Users\User\go\src\e

File: e.go

Decode Lines: 53 to 93 (40)

Decodefunc1 Lines: 70 to 155 (85)

FromB64 Lines: 93 to 121 (28)

Decrypt Lines: 121 to 144 (23)

HashStr Lines: 144 to 150 (6)

RandomHashString Lines: 150 to 153 (3)

init Lines: 155 to 155 (0)

Package main: C:\Users\User\go\src\m

File: m_main.go

main Lines: 17 to 21 (4)

TryDoMain Lines: 21 to 31 (10)

TryDoMainfunc1 Lines: 22 to 44 (22)

DoMain Lines: 31 to 43 (12)

TryDoIter Lines: 43 to 57 (14)

TryDoIterfunc1 Lines: 44 to 166 (122)

DoIter Lines: 57 to 100 (43)

GetU Lines: 100 to 117 (17)

OnData Lines: 117 to 146 (29)

Execute Lines: 146 to 151 (5)

GetHttp Lines: 151 to 160 (9)

CreateTempFileName Lines: 160 to 164 (4)

init Lines: 166 to 166 (0)

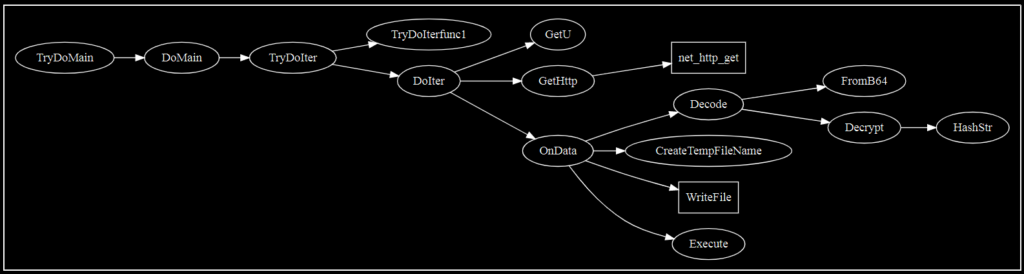

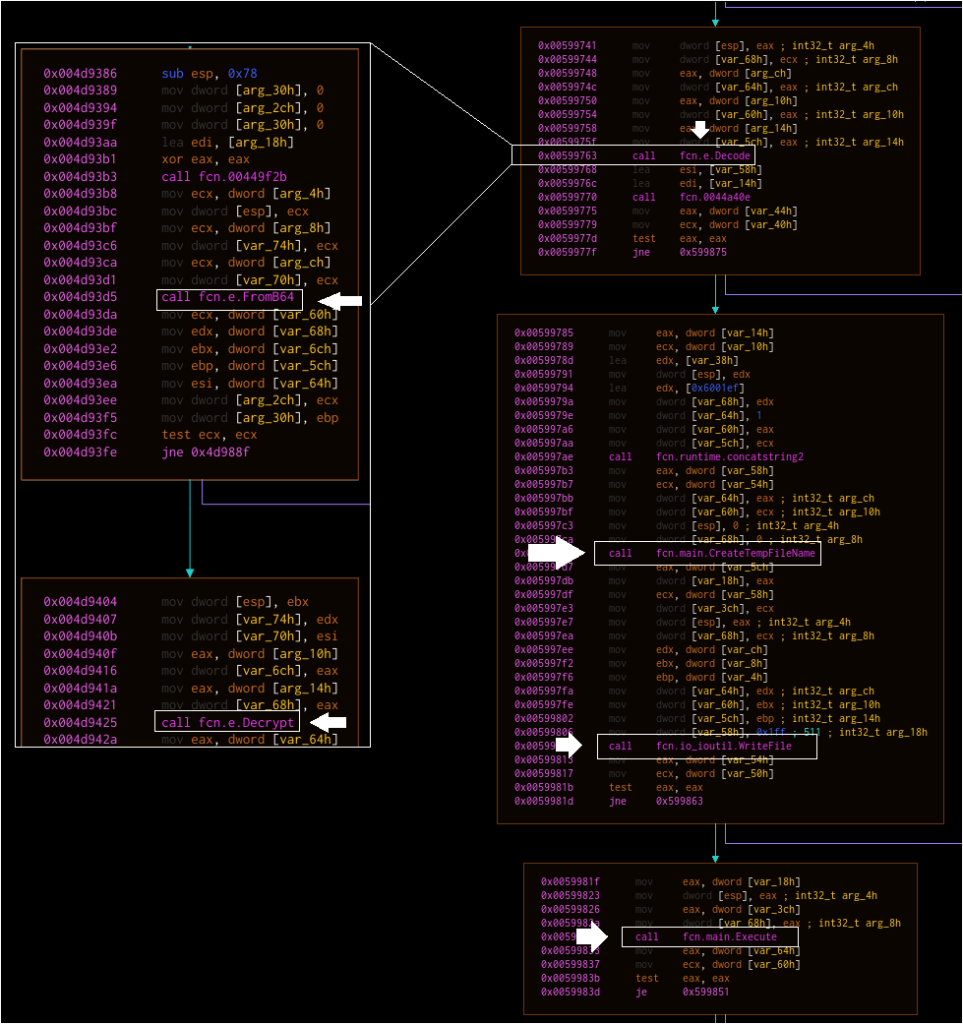

A few things should stand out. First, the “e” package appears to be reused, alongside all of the decoding and decryption functions. However, this is clearly not a “copy” of the initial dropper. The primary package has new functions, such as GetHttp, OnData, CreateTempFileName, and execute. Using the same strategy as before, we can map some key functions out.

As with the previous graph, the code structure (for this particular example – again, most samples are less linear) is such that we can read left-to-right and top-to-bottom. We might expect that:

1. The malware runs GetU. Perhaps this obtains the username (it does not, but that was my initial guess).

2. The malware establishes an HTTP connection.

3. The malware checks to see if it gets a response, and if so, Base64 decodes and then decrypts that response.

4. The malware creates a filename for a target in the Temp directory.

5. The malware writes the decoded data to this file.

6. The malware executes this file.

For this example, I opted to use radare2 + redress, followed by piping the output of the “afl” function to a file. With some Notepad++ regex, I used the function addresses to make a basic x96dbg script to re-label all of the addresses. See here for an example from another analyst (replacing cmt with lbl). I mainly did this for performance reasons, and to demonstrate an additional option readers.

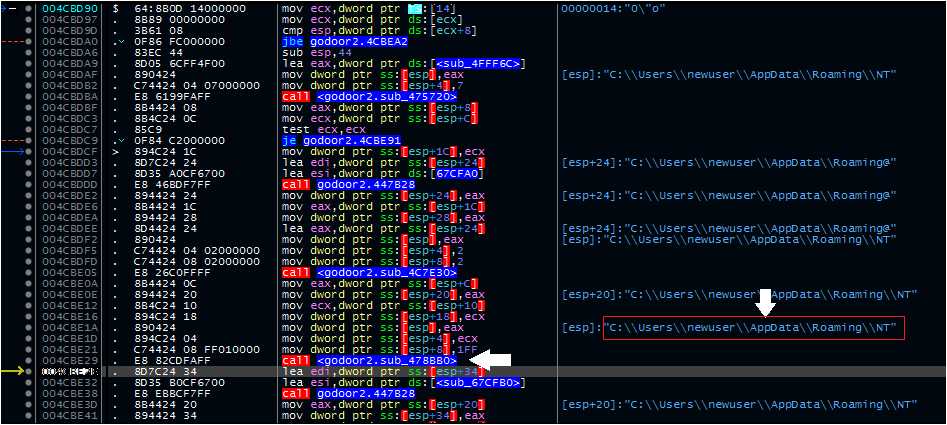

Debugging the malware, we can get through the GetU function before we start to run into some obstacles that will hinder a full analysis. Recall that we hypothesized that GetU could return the username. It actually creates the string for the GET request sent to the C2 server:

Right click and open in a new tab to zoom in a bit. The GetU function pulls one of five hardcoded C2 servers and appends an identifier string to it:

hxxp: // 176.53.11[.]130/aspnet_client/system_web/4_0_30319/update/DefaultForm.txt

hxxp: // 82.222.188[.]18/aspnet_client/system_web/4_0_30319/update/DefaultForm.txt

hxxp: // 130.25.10[.]158/aspnet_client/system_web/4_0_30319/update/DefaultForm.aspx

hxxp: // 41.205.61[.]221/aspnet_client/system_web/4_0_30319/update/DefaultForm.aspx

hxxp: // 5.150.143[.]107/aspnet_client/system_web/4_0_30319/update/DefaultForm.aspx

One of these values, boxed in red above, remained consistent through different runs of the malware. This value, 881456fc, also appears in VirusTotal runs of the malware in the behavior tab. If the file is run with a command line argument (as the runkey would cause), this value is appended with that argument. If not, the value is appended with “no” instead. One possibility is that this serves as a campaign ID and a device identifier.

At this stage, the analysis ran into some hurdles that could not be overcome. The malware didn’t appear to call out to the C2 server during the GetHTTP call, limiting confirmation of the remainder of the suspected functionality. Still, we can make some pretty strong inferences from the final call of the workflow, OnData:

The workflow strongly suggests that something is Base64 decoded and decrypted, written to disk at a generated location, and then executed. Symantec’s original report suggested that several other backdoors were deployed against victims. It is therefore possible that Goodor was used to deliver a tool such as a screen grabber, the Karagany backdoor, or one of several other payloads.

Concluding Thoughts

A few simple contemporary tools make analyzing Golang malware significantly easier than it was in the past, particularly for those lacking access to premium tools such as IdaPro. Radare2, Cutter, and Redress can combine to create a workflow where the user can rename Golang functions, navigate a graph, and debug malware significantly easier than in the past.

During this research, I ran a retrohunt to try to identify additional samples that contained the same encoding functions or matched other function names from the dropper and payload. Unfortunately, while I found other hashes, none were “new.” This may have been a one-time use tool from the threat actor, or the function names may have been renamed in different versions.