Recently, a VirusTotal submitter uploaded a file that was digitally signed with the same certificate as two previously reported Lazarus tools. Like one of those tools, this newly uploaded malware appears to act as an injector, although it behaves significantly differently.

This blog post offers a brief analysis of the features and purpose of this injection tool, as well as a comparison with a previously identified injection tool that behaves significantly differently and likely serves a different operational purpose.

Update 20 October, 2019: A small section towards the bottom of this post has been updated to reflect this malware’s strong resemblance to a file described in a US-CERT Report in late 2018. The file in that report served as an injector for the FASTCash AIX malware. Given this file’s similarity, it is highly likely that this file is intended to perform a similar function, but on a Windows environment.

MD5: 89081f2e14e9266de8c042629b764926

SHA1: 730c1b9e950932736fc4b02cbdb4e4e891485ac2

SHA256: 39cbad3b2aac6298537a85f0463453d54ab2660c913f4f35ba98fffeb0b15655

Curiously, this file contains a compilation stamp of 2018-06-13 06:17:06 but was digitally signed on 7:43 AM 6/20/2019. The digital signature of this file matches the signature used on two Lazarus tools discussed in open source and on this blog. These factors suggest that the tool may have been developed last year but continues to be deployed in contemporary intrusions, which could explain the recent signing dates.

Operation

The injector expects four command line parameters to be present on operation:

– The path of the injector, which under normal circumstances is automatically part of the command line

– An integer value (1 or 2) that specifies the operational mode (inject or eject)

– A process identifier (PID) value that specifies a target process

– A path to the DLL to be injected into the target PID

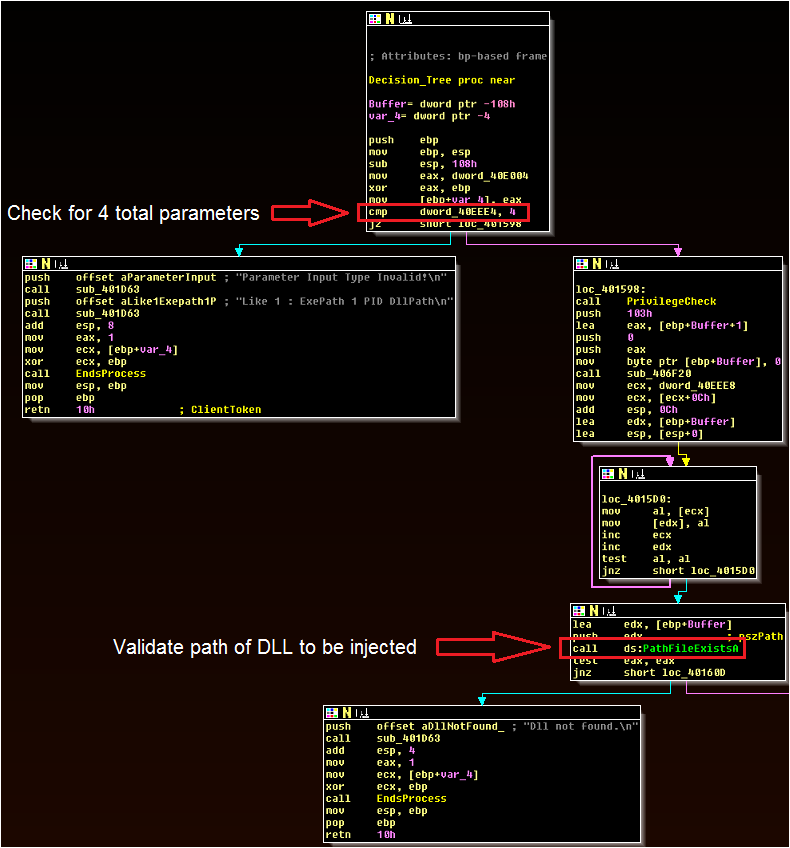

The malware first checks that there are a total of four parameters present before validating their content. Next, it uses the PathFileExistsA API call to validate the path to the DLL to be injected. The injector also contains debugging messages. These items are all visible in the image below.

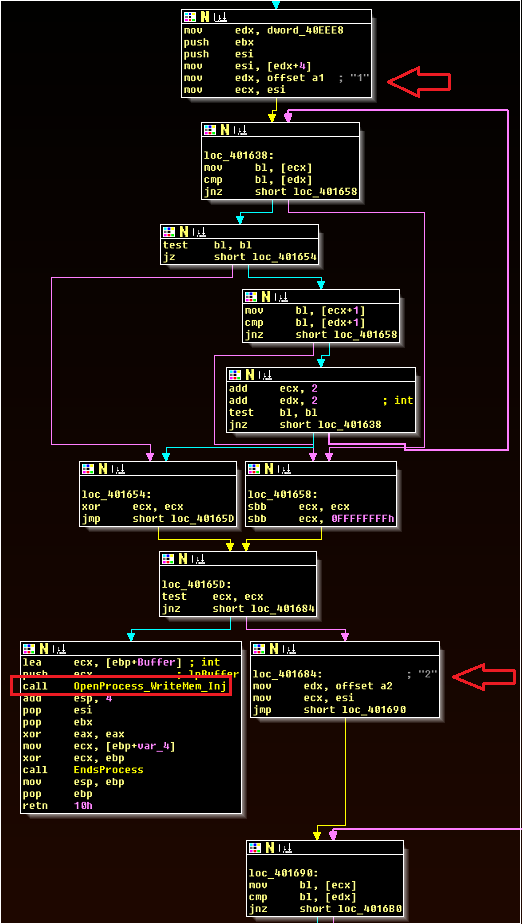

Next, the malware checks that an integer has been supplied as a PID and that either the integer 1 or the integer 2 have been supplied for the operational argument. Curiously, dynamic debugging suggests that the PID check will still pass as long as an integer is the first digit (for example, passing “94a” will still cause the malware to attempt to inject or eject a DLL from a process with an invalid PID, although this will fail the OpenProcess attempts).

The malware operates in two one of two ways:

1 – Will attempt to open a process, write a target DLL to virtual memory, and run the DLL by creating a thread

2 – Will attempt to open a process, enumerate its modules, and remove the target DLL if found in the process

The process for injecting the payload is relatively routine: The injector passes the specified PID into the OpenProcess API, allocates a section of memory via VirtualAllocEx, uses WriteProcessMemory to write the DLL to this location, resolves the NtCreateThreadEx API via GetProcAddress, and creates a thread to run the payload.

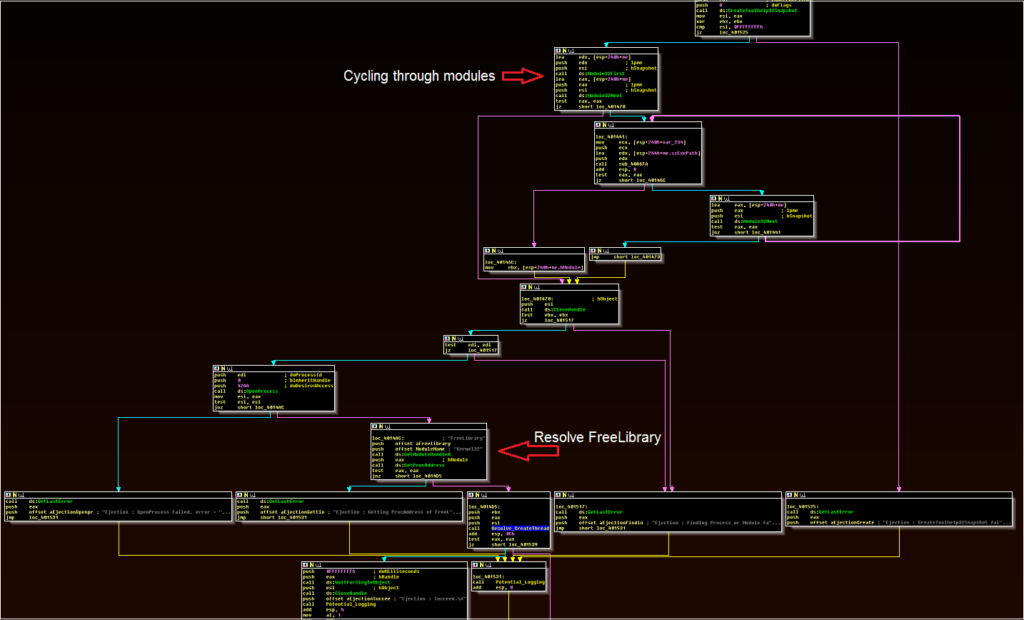

The process for (and concept of) ejecting the payload is a bit more notable. The malware passes the specified PID as an argument for CreateToolHelp32Snapshot, which will also enumerate the modules present in the target process. The injector will then use Module32First and Module32Next to cycle through these modules, checking if any match the file path of the DLL specified upon execution. If found, the malware resolves the FreeLibrary API call and uses this to remove the module.

Following the attempt to inject or eject the payload, the malware will terminate. The malware also has a logging function, which will try to write timestamped logging messages at c:\Intel\tmp3AC.tmp that indicate whether certain tasks passed or failed. Note that these are not the same as the debugging messages. Examples include:

[2019-10-01 19:07:51.294] Injection : Succeed

[2019-10-01 19:46:11.821] Ejection : Finding Process or Module failed. error = 18

This blog notes that this logging file path and format generally match previously observed paths and formats for DPRK tooling.

Differences with Previously Reported Injector

As noted earlier, while this file’s purpose is to inject payloads into a target process, there are some key operational and design differences between this malware and a previously reported one.

– The file analyzed in this post does not contain a way to delete payloads from disk, whereas the previously reported injector does.

– The file analyzed in this post allows the user to specify a target process, rather than defaulting to explorer.exe

– The file analyzed in this post contains significant debugging and logging messages.

– The previously analyzed file used a file size check to ensure that the injected DLL contained data, whereas this file does not.

While the files are highly likely part of the same adversary’s toolset, these differences do suggest that the may serve different purposes and may have been written by different authors, although that is speculation given the lack of additional context currently available for the file analyzed in this post.

Update 20 October 2019: As noted in the original version of this post, this file operates significantly differently from the previously identified injector. One of the biggest differences is in functionality- the file described in this post can inject a payload into a specified process.

A simple comparison of the features in this malware with a file described in a US-CERT Report from late 2018 reveals that they serve nearly identical purposes (but for different operating systems). In that report, researchers describe an injector used to deploy a payload that hooks the send and receive functions of a target process in order to intercept ISO 8583 financial messages. This would explain the need to specify the process by PID, as the process name might vary from environment to environment.

The file described by US-CERT is designed for UNIX systems, whereas the file in this blog post is designed for Windows systems. This would suggest that the threat actors responsible likely have a FASTCash payload for Windows operating systems as well.