In an earlier post, this blog examined malware from a DPRK-affiliated campaign targeting security researchers. Since the initial public post about this activity from Google, multiple vendors have corroborated and supplemented the technical details in this attack.

Whereas the previous post examined a DLL file delivered via social engineering and VisualStudio, this post examines the inner-workings of a malicious .sys file likely delivered through a watering hole. In addition to reverse engineering, this post offers possible threat hunting avenues for identifying data associated with this file hidden in the registry of a compromised system.

For those purely interested in the hunting portion of this post (the malware reads, and likely executes, data from the registry), click here to skip ahead. As a disclaimer, the hunt workflow proposed is merely hypothetical, and should not be considered any sort of official security guidance.

(2/1 Update, Stage 2 can be found here)

Technical Analysis

Filename: helpsvc.sys

MD5: ae17ce1eb59dd82f38efb9666f279044

SHA1: 3b3acb4a55ba8e2da36223ae59ed420f856b0aaf

SHA256: a4fb20b15efd72f983f0fb3325c0352d8a266a69bb5f6ca2eba0556c3e00bd15

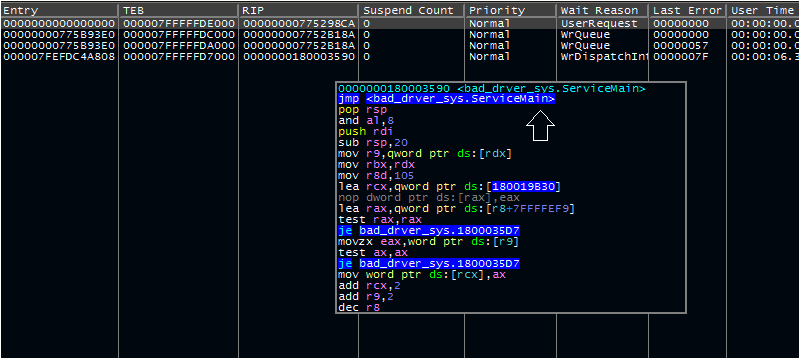

Examining this file in IDA reveals that this file is a DLL likely intended to run as a service, given one of its exports (ServiceMain) and several of its imports (RegisterServiceCtrlHandlerW, SetServiceStatus). There are a few routes available for debugging a file like this- ultimately, I settled on the following steps:

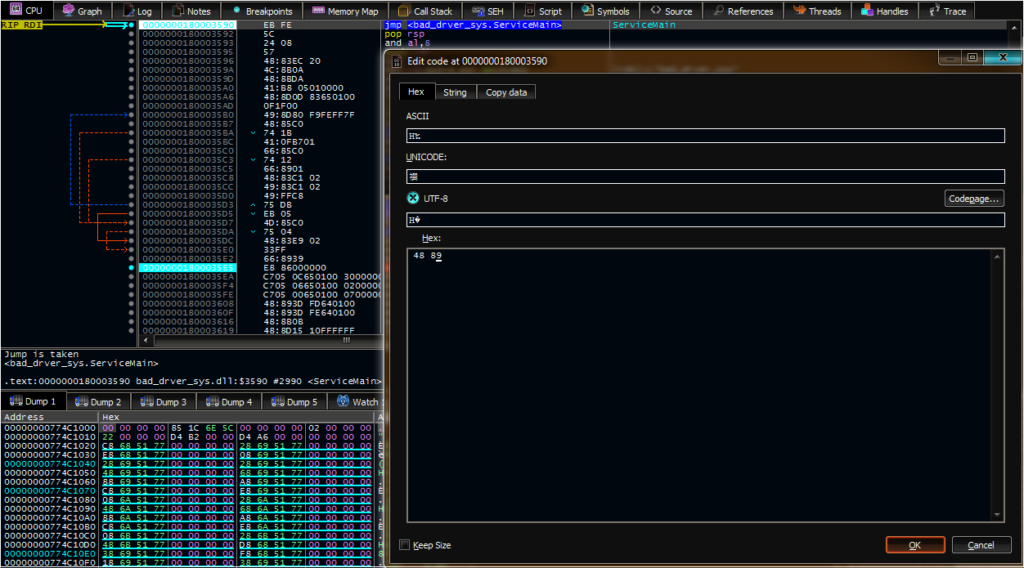

1) Edit the first two bytes of ServiceMain to EB FE, creating a loop that allows us to attack, resume, and debug it

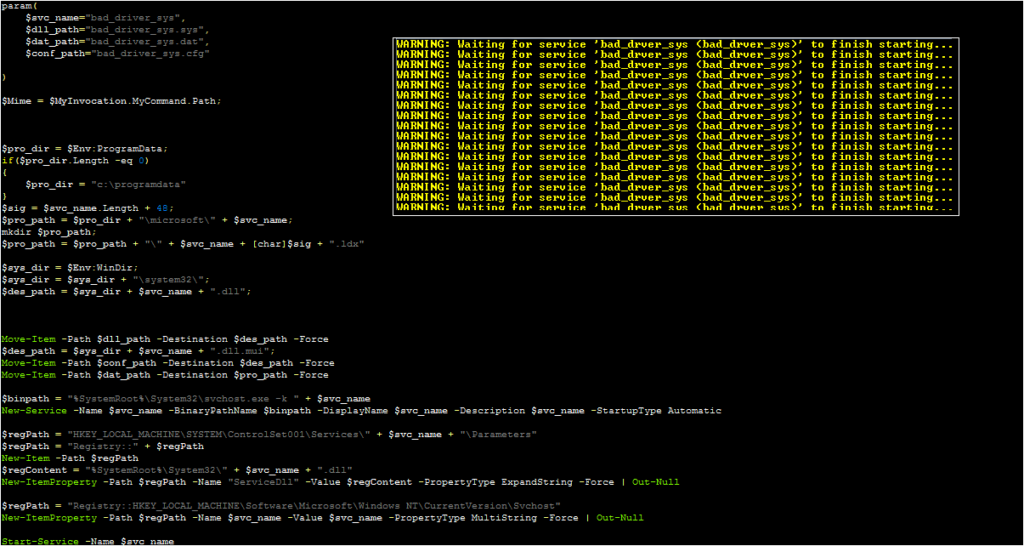

2) Modify a previous service-installing PowerShell script from a different DPRK adversary

3) Run PSExec with system-level permissions

4) Use PSExec to run x64dbg, giving it the permissions needed to step into the running service and begin debugging

The PowerShell script was selected for simplicity; in short, previous research showed that it can be used to install a DLL as a service. This current task requires that a DLL be installed as a service. Thus, it did the job of handling the appropriate registry modifications.

This PowerShell script will start a new copy of svchost, which in turn runs this new service. The PowerShell script will also indicate that it is waiting for the service to start; this is expected, as several key routines within the malware occur before the ServiceStatus is set.

By stepping into the svchost process, resuming this process, and selecting the correct running thread, we can place a breakpoint on the infinite loop and re-patch the malware to the original instructions.

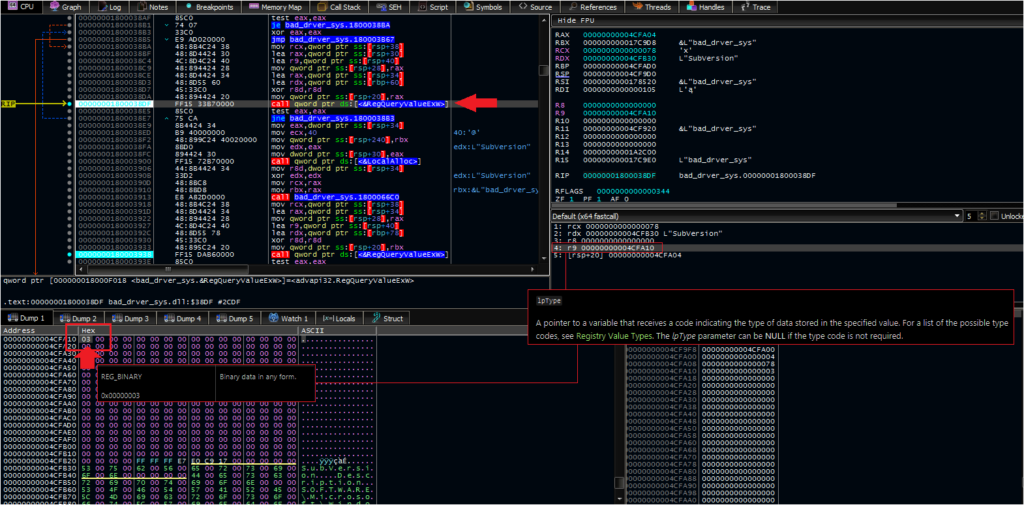

Once this patch is in place, the malware will resume its expected behavior. First, the malware steps into a function and begins placing data in memory in a similar fashion as the previously analyzed DLL. In this instance, the malware decrypts three values:

– SubVersion

– Description

– Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\KernelConfig

This third value is a registry entry. The malware attempts to open this value under HKLM; however, this value does not exist, and the malware does not create it. This strongly suggests another mechanism, such as code launched via browser exploit or another dropper, places this data in the registry.

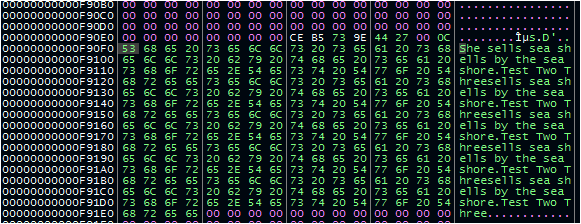

If the malware does open this key, it attempts to read data within values named SubVersion and Description (the two other decrypted strings). For the purposes of continuing the analysis, I created this registry key and these two entries, with dummy values in each location. The values chosen were random, which led to some trial and error to determine their possible purpose.

After some attempts, it seemed that anything longer than four bytes in the SubVersion entry led to an error during the malware’s execution. Specifically, the malware returned 0xEA and gracefully terminated. In addition, the malware seemed to hit an exception when tested with exactly four bytes. I picked a random two-byte value to allow it to proceed.

For the Description entry, I used human-readable sentences and words to make them easier to track.

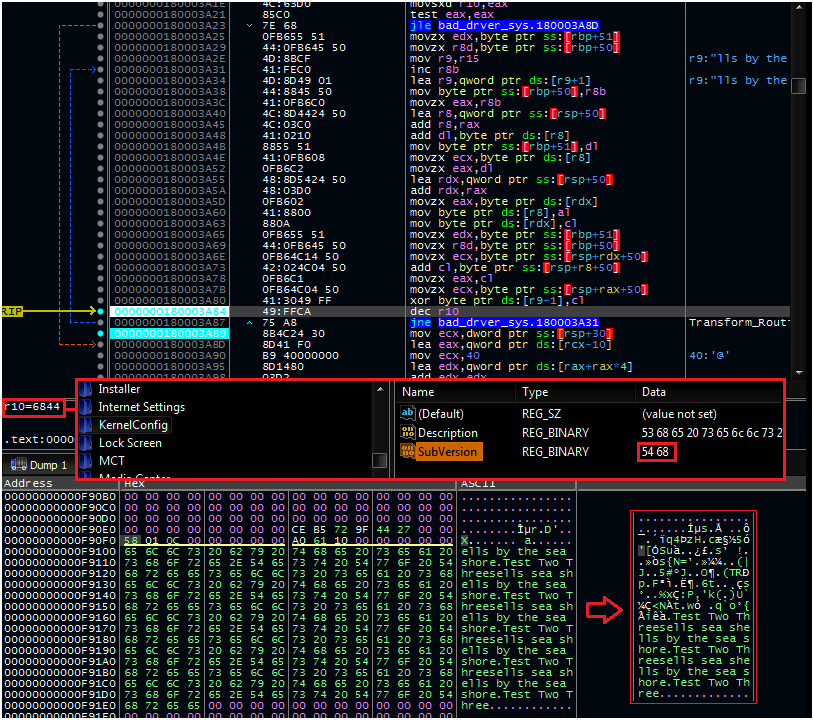

After reading the Description value, it begins transforming this data through a loop; however, the number of repetitions of the loop is not dependent on the length of the Description data. Instead, the malware uses a value that appears to be [10 in hex, 16 in decimal] fewer than the value stored in the SubVersion registry key. In addition, the malware truncates 16 hex characters off of the start of the data being transformed.

After this transformation, the malware steps into a function that checks for the presence of a PE header (MZ) and allocates memory. This function also contains a call to a dynamic API resolution routine similar to the previously examined DLL associated with this campaign; unfortunately, neither of these routines could be properly examined during this analysis (likely due to the lack of a proper expected payload or other similar factors).

Following these function calls, the malware starts the service.

Second Stage Payload

After publication, an analyst who wished to remain anonymous pointed me to a copy of the missing registry data. I left the previous writing intact, as the analytic method may prove useful to future readers. Below contains some brief technical analysis of the payload decrypted from the registry.

Name: KernelConfig Registry data (approx. 2mb)

MD5 7904d5ee5700c126432a0b4dab2776c9

SHA1 79bd808e03ed03821b6d72dd8246995eb893de70

SHA256 7c4ea495f9145bd9bdc3f9f084053a63a76061992ce16254f68e88147323a8ef

This file can be given a .reg extension, which will import the data into the device’s registry. With this data in place, the malware properly continues its routine and decrypts and runs an executable payload.

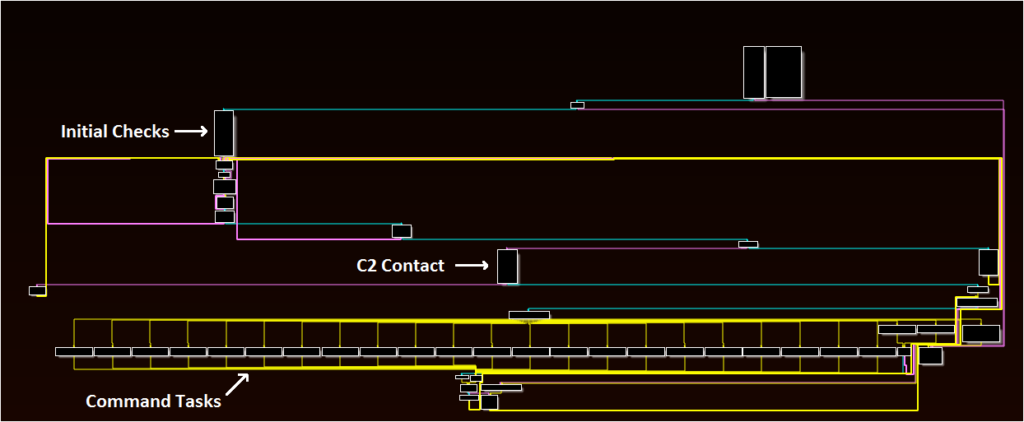

Unlike the DLL analyzed in a previous post that functioned as a downloader, this file has a wide range of additional features. This second-stage file begins by dynamically resolving a very large list of APIs from Windows libraries such as kernel32, advapi, ntdll, userenv, and others. The malware then:

– Performs a startup check

– Communicates with the C2 server (using the OpenSSL library)

– Uses a Case-Switch workflow to carry out commands

The startup check (and other routines within the malware) use the same in-memory decoding routine to decrypt hidden strings containing important values for the malware’s execution. In this case, the malware can use this routine to decode three C2 servers for communication. In addition, it can write to and read data from the a key located at HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\DriverConfig.

After this, the malware will contact a C2 server. The decoded C2s for this sample are:

hxxp: // www.colasprint[.]com/_vti_log/upload.asp

hxxps: // www.dronerc[.]it/forum/uploads/index.php

hxxps: // www.fabioluciani[.]com/es/include/include.asp

The malware supports a wide range of commands and actions. Some of the highlights are:

– Writing files to the disk and executing them

– Collecting network adapter information

– Enumerating running processes and there start times

– Collecting drive and file info

– Enumerating items in a directory

– Creating a process

– Terminating a process

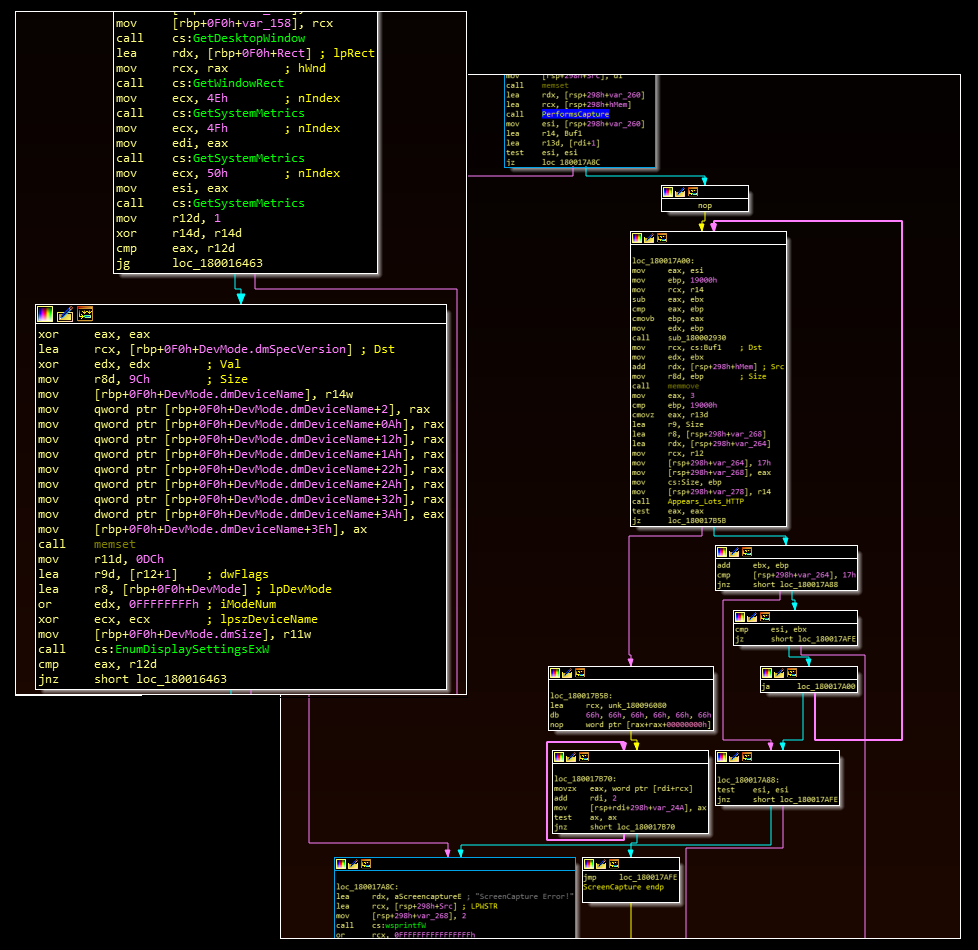

– Performing a screen capture

Based on these commands, the tool is likely used to conduct reconnaissance and potentially to triage a device before taking further steps in the environment.

Hunting Possibilities

When looking for malware like this on a device or across a network, an initial instinct might be to search for known malicious registry key values. At the time of this writing, the only known registry entries for this malware are the ones described above at KernelConfig; however, the attackers could easily change this (or could have deployed malware that uses different values against targets that have yet to identify the infection).

From a defensive perspective, however, two things work in our favor:

– Registry key values are usually small

– Code needed to execute a malicious workflow is usually larger than a registry key

Given these two facts, one option is to examine the registry for any uncharacteristically large values. As this post will shortly show, this is merely a starting point for hunting; however, it’s an effective one.

As an experiment, I pulled malware samples from previous (unrelated) adversary activity. An uncompressed meterpreter shell took up just under 1 kb (1,000 bytes). A compressed version took up approximately 300 bytes. I consider these to be a reasonable estimate for the lower-bounds of an executable payload size that an attacker would use.

I then modified an open-source PowerShell script to enumerate the every key and value in the CurrentVersion location of HKLM. In a real scenario, I would likely try this against the entire registry.

Get-ChildItem -Recurse registry::hklm\software\microsoft\windows\currentversion\ | foreach-object {

$path = $_.PSPath

$_.Property | foreach-object {

$name = $_

$data = get-itemproperty -literalpath $path -name $name |

select -expand $name

$dl = $data.length

#[pscustomobject]@{value=$name; data=$data; key=$path}

add-content -path "c:\users\[user]\desktop\dump2.txt" -value "$path¿$name¿$dl"

}

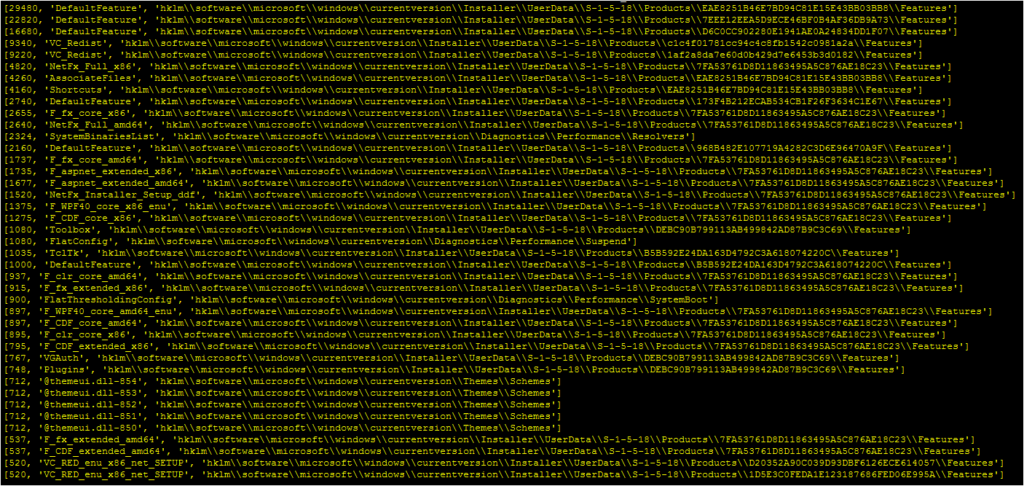

}This produces a CSV file of approximately 194,000 values (I used the upside down question mark as a delimiter and edited out excess commas and quotation marks) with the key path, key name, and length of the data. In theory, sorting these by the largest keys should show outliers. I used the following Python code:

import csv

import re

keys = []

with open("c:\\users\\[user]\\desktop\\dump.txt", encoding="utf-8") as csvfile:

reader = csv.reader(csvfile, delimiter=",")

for line in reader:

if int(line[2]) > 199:

demo_value = re.sub(".*?hklm","hklm",line[0])

else:

demo_value = line[0]

keyadd = []

keyadd.append(int(line[2]))

keyadd.append(str(line[1]))

keyadd.append(demo_value)

keys.append(keyadd)

#print(len(keys))

keys.sort(reverse=True)

for item in keys:

print(item

Out of 194,000 entries within the CurrentVersion section of the HKLM hive:

– A 100KB payload such as the one analyzed in the previous post would easily top the list

– A 1KB uncompressed meterpreter shell would also top the list

– A 300 byte compressed meterpreter shell would be harder to identify, ranking right around the top 100

As mentioned above, this is just a starting point. Additions to this workflow, such as generating the last modified time of the registry key, would likely greatly improve this workflow. Parsing the data for character entropy would also likely improve the accuracy. Even without these two changes, however, a malicious payload stored in a registry value would easily rank in the top 99% of values.

Update 2/1/2021: Analysis of the proper, adversary-intended KernelConfig value shows that the registry data is approximately 2mb. Registry data of this size would likely rank at the top of any registry dump in this proposed workflow.