Last month’s post on this blog examined a backdoor previously thought to be associated with Emissary Panda (APT27). Recent reporting has instead shown that the HTTP listener examined is likely affiliated with Turla. That post has been updated with the corresponding corrections.

This post is a granular examination of a payload alluded to in a Palo Alto report that is tied to Emissary Panda with much higher confidence. While the payload wasn’t available for analysis in that report, VirusTotal pivoting at the time produced the matching file.

Filename: PYTHON33.hlp

MD5: 19c46d01685c463f21ef200e81cb1cf1

SHA1: ac4a264a76ba22e21876f7233cbdbe3e89b6fe9d

SHA256: 3e21e7ea119a7d461c3e47f50164451f73d5237f24208432f50e025e1760d428

This file is expected to be part of a DLL side-loading chain that involves a component of the legitimate Sublime text editor (plugin_host.exe, also available on VirusTotal: f0b05f101da059a6666ad579a035d7b6) and a malicious DLL that this file will sideload:

Filename: PYTHON33.dll

MD5: bc1305a6ca71d8bdb3961bfd4e2b3565

SHA1: f189d63bae50fc7c6194395b2389f9c2a453312e

SHA256: 2dde8881cd9b43633d69dfa60f23713d7375913845ac3fe9b4d8a618660c4528

Preparation

If all three of these files are placed in the same folder with the correct filenames, plugin_host.exe will sideload PYTHON33.dll, which will decrypt and decompress the PYTHON33.hlp file into a DLL. The workflow for this is similar to (but not identical to) previous reporting from NCC group regarding an earlier version of this malware. This post will thus not go into detail regarding this process, but makes the following recommendation for analyzing these components:

1) Patch the PYTHON33.hlp file (which is a block of shellcode) by prepending an infinite loop (EB FE) to the file via a hex editor

2) Run plugin_host.exe normally (i.e. not in a debugger). This will sideload the DLL and load the shellcode, but will hold it in an infinite loop without executing any commands

3) Attach a debugger (e.g. x96dbg) to this running process and step through until the payload is decoded in memory, as you would any other shellcode samples. In this case, a good breakpoint to set is would be at the entry to “CommandLineToArgvW”

The breakpoint in step 3 wouldn’t be obvious during the initial examination of this file, but this blog mentions it here as a shortcut to facilitate analysis of this file. The DLL can also be dumped at this stage for concurrent static analysis in IDA.

Payload

The Palo Alto report mentions similarities between the loading and decrypting process for this file and the loading and decrypting process for a file previously analyzed (but not provided) by NCC Group. NCC Group provided a high-level overview of that payload’s capabilities. This overview serves as a framework for “what we might be looking for;” specifically, NCC group mentions the following:

– An execution workflow determined by the number of specified parameters

– Process injection into svchost

– A series of keys written to the registry in a unique way

– A basic persistence mechanism (HKCU runkey) + service creation

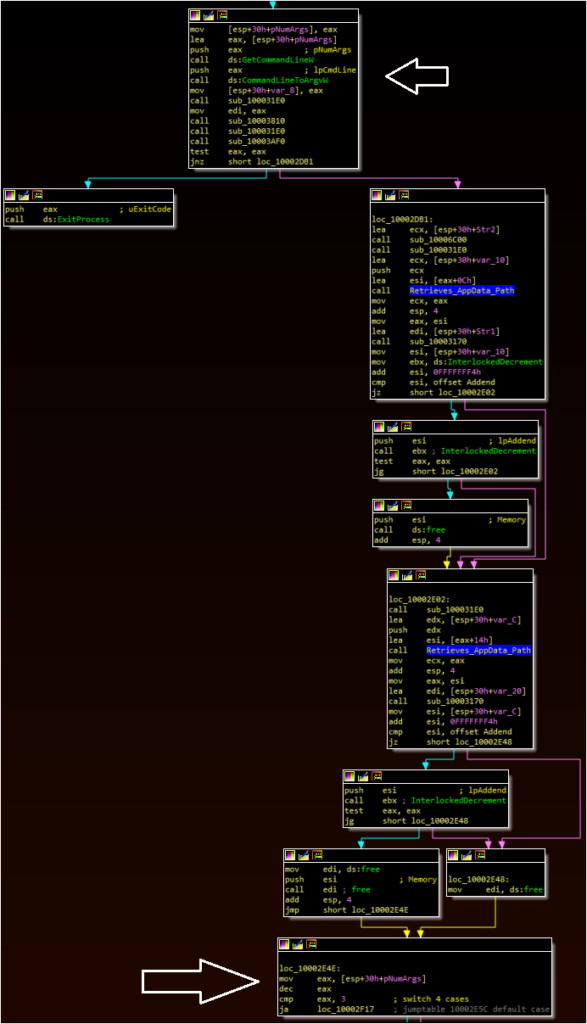

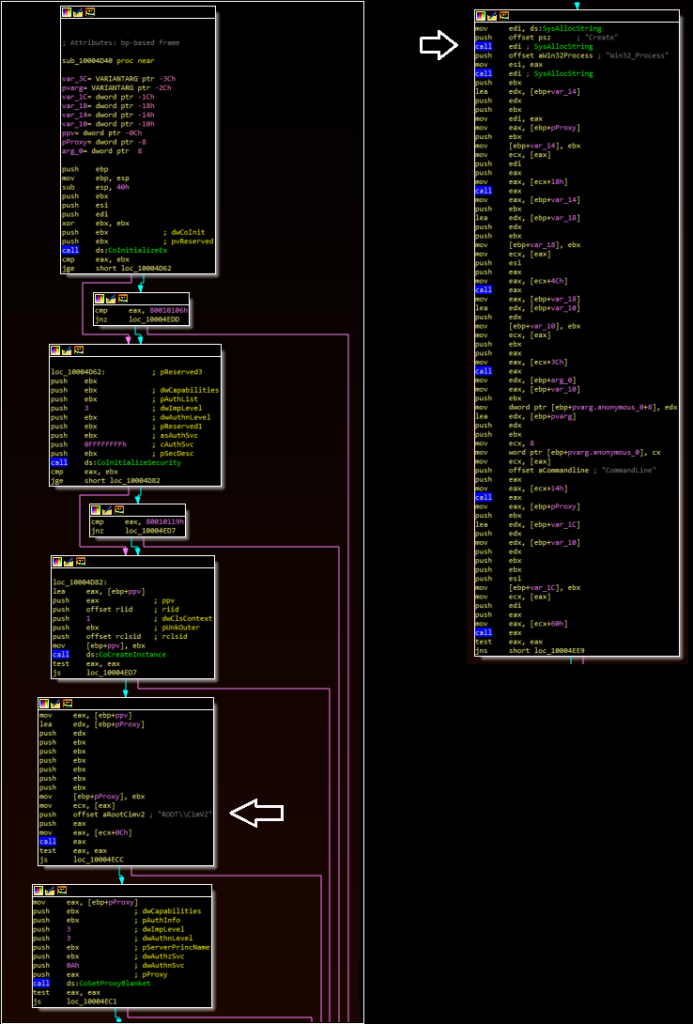

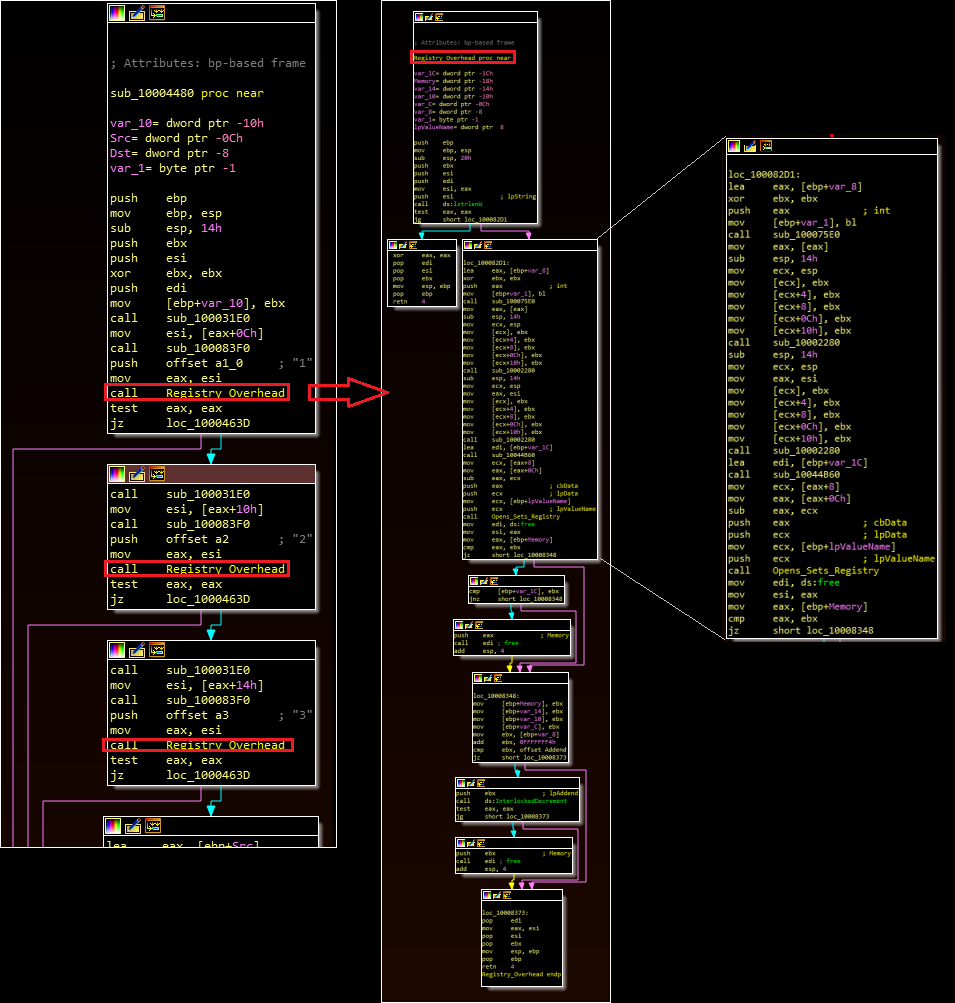

This offers a big head-start for analysis. First, the malware calls GetCommandLineW followed by CommandLineToArgvW. Per MSDN documentation, this second call “parses a Unicode command line string and returns an array of pointers to the command line arguments.” The “number of pointers in this array is indicated by pNumArgs.” The screenshot below shows these two API calls at the top, followed by a comparison between pNumArgs (decreased by 1, for the case statement) and the value “3:”

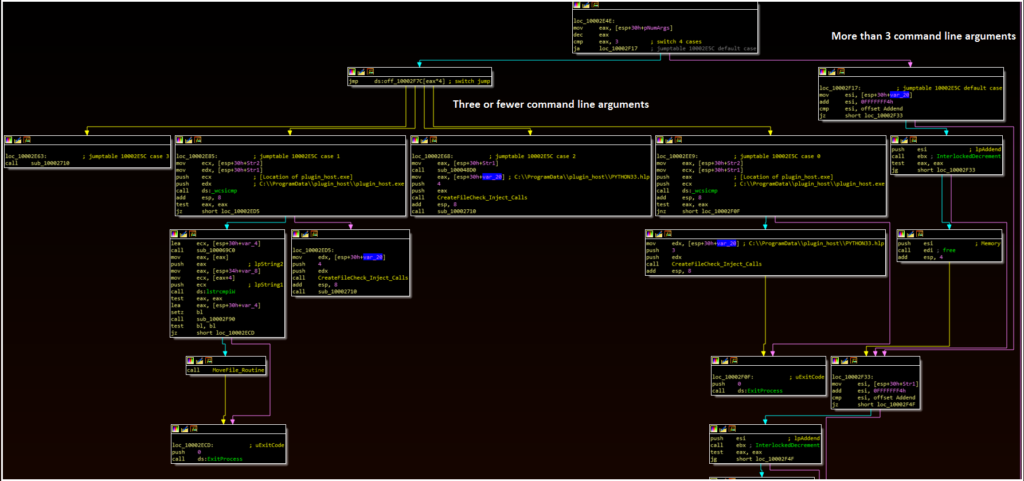

If EAX is greater than 3, (i.e. if there are more than three command line arguments), the malware will jump to the default case rather than cases 0-4, will return to the calling function, and will terminate without taking any action. If EAX is less than or equal to 3, it will jump into one of the available cases:

As always, right click and open the image in a new tab to enlarge. Additional labeling has been added, including string labeling that would be visible during dynamic analysis in a debugger. At this stage, we can begin exploring the cases.

Case 0

A good way to explore these cases to take a snapshot just prior to the EAX comparison, and then set EAX to the value of the case to be examined. In Case 0, the malware:

– Moves a string representing the location of the currently running executable (plugin_host.exe) to EAX

– Moves a string containing “C:\\ProgramData\\plugin_host\\pluginhost.exe” to ECX

– Pushes these two values to the stack

– Uses wsicmp to compare these two values

– Jumps to an “ExitProcess” call if these two values do not match

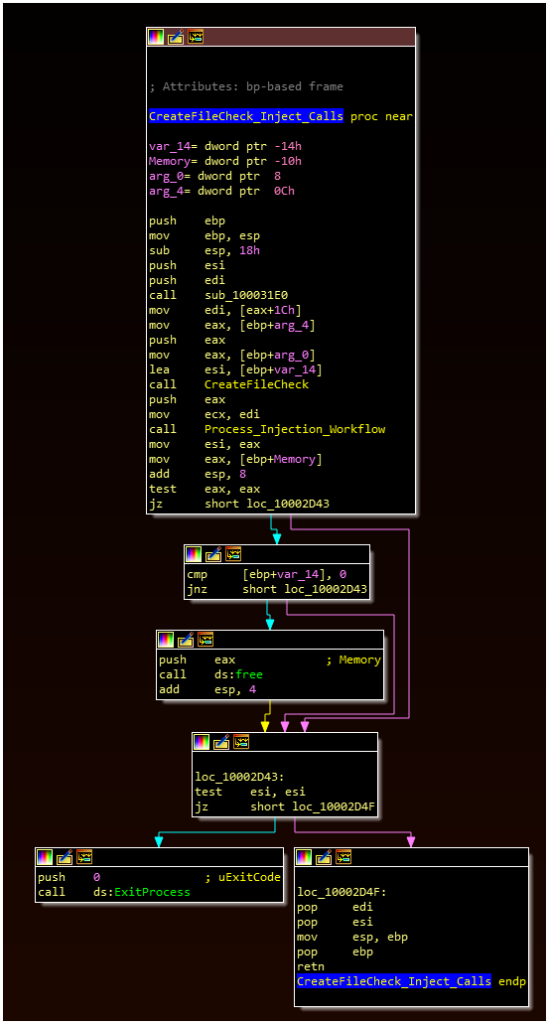

If these two values do match, the malware will move to a function call referenced in several locations, labelled in the above IDA screenshot as the CreateFileCheck_Inject_Calls. As this label would suggest, there are two primary subcomponents of this call, labelled below as CreateFileCheck and Process_Injection_Workflow.

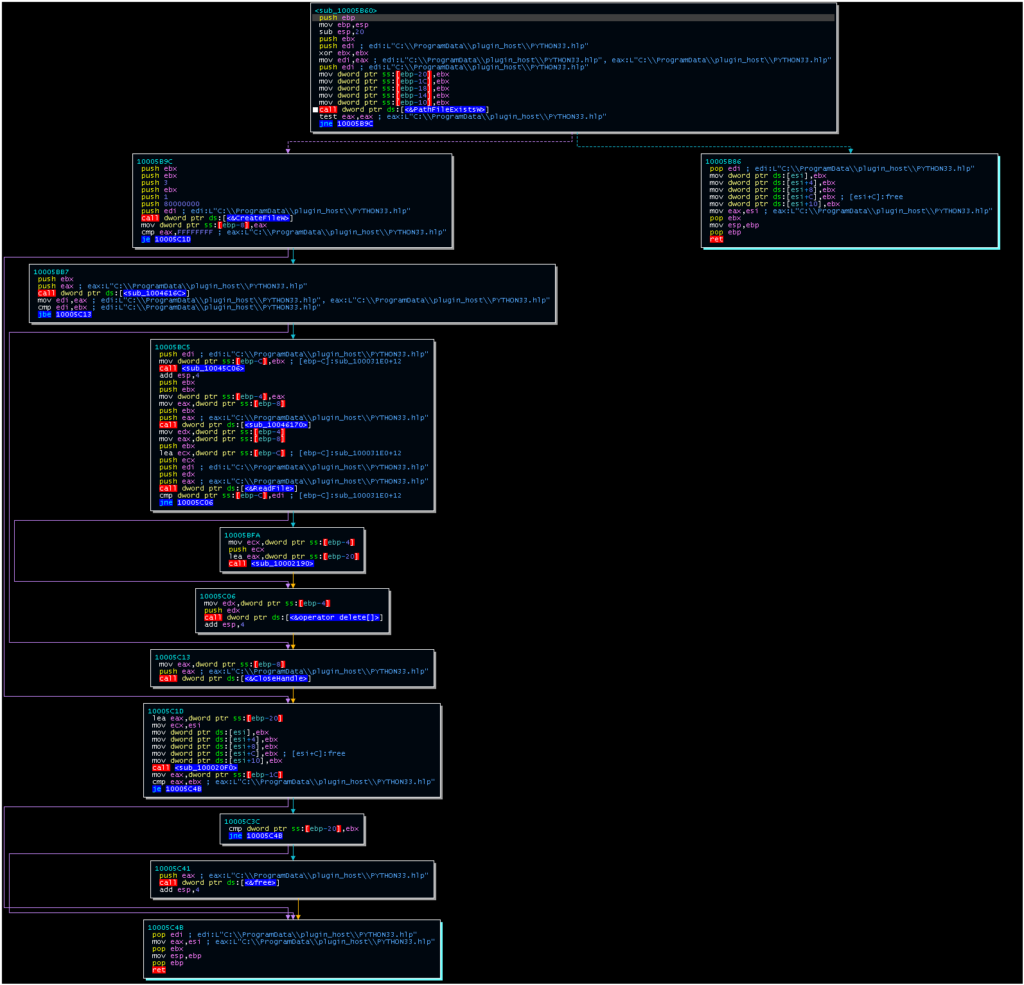

The CreateFileCheck subroutine will use the PathFileExistsW and CreateFileW APIs to check if the malware can open C:\\ProgramData\\plugin_host\\PYTHON33.hlp:

The next function, not pictured here due to space constraints, will take the following actions:

– Locate and spawn a suspended copy of svchost.exe

– Allocate an executable section of memory

– Write PYTHON33.hlp to this section of memory

– Create and resume a thread at this location

This is a common workflow for process injection. The parent process will then terminate. Thus, Case 0 can be summarized in the following way:

– Ensure that plugin_host.exe is running from the correct directory

– Ensure that PYTHON33.hlp is inside of this directory

– Create a suspended svchost.exe process

– Re-write a copy of the payload into this process

– Terminate

Case 1

Case 1 can be thought of as Case 0 with added contingencies. Case 1 begins with the same string comparison, ensuring that the malware is running from the “C:\\ProgramData\\plugin_host\\” directory. If this comparison is successful, the malware will run the same check for PYTHON33.hlp and process injection routines described in Case 0, followed by the “core functionality” routine (described later).

Unlike Case 0, if the file is not running from the correct subdirectory in ProgramData, the malware does not terminate; instead, it performs what is labelled as the “MoveFile_Routine” in the IDA case picture. This workflow:

– Moves the necessary components for the malware to run into the ProgramData\\plugin_host\\ directory

– Executes plugin_host.exe using WMI

Case 1 represents a more flexible workflow for starting the malware for the first time.

Case 2

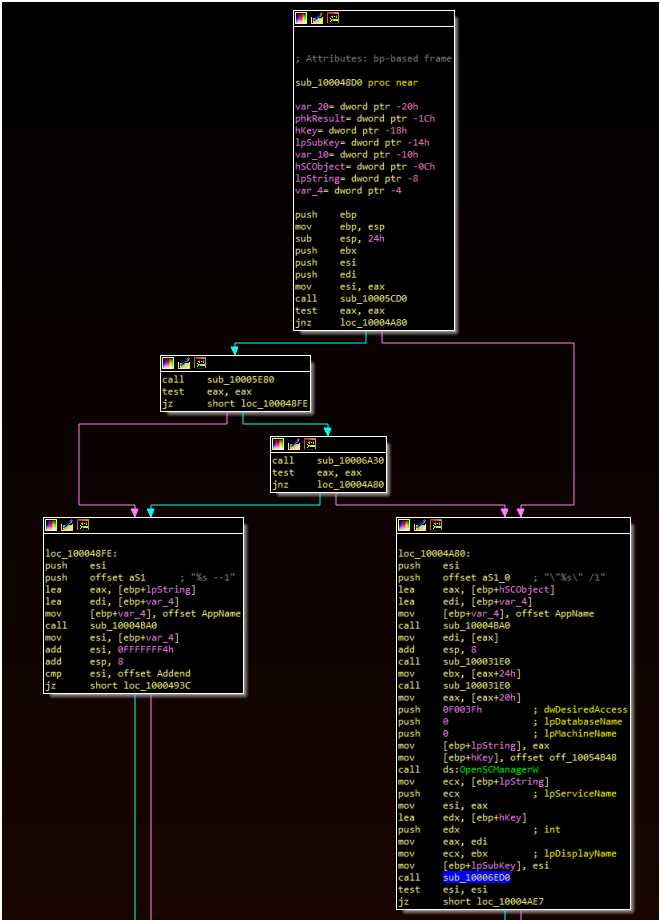

Case 2 contains three parts, in the following order:

– A new call not yet analyzed

– The same CreateFile check and ProcessInjection calls

– The “core functionality” call discussed in Case 3

The new call is actually fairly simple. This function performs a permissions check, and takes one of two branches depending on the permissions available:

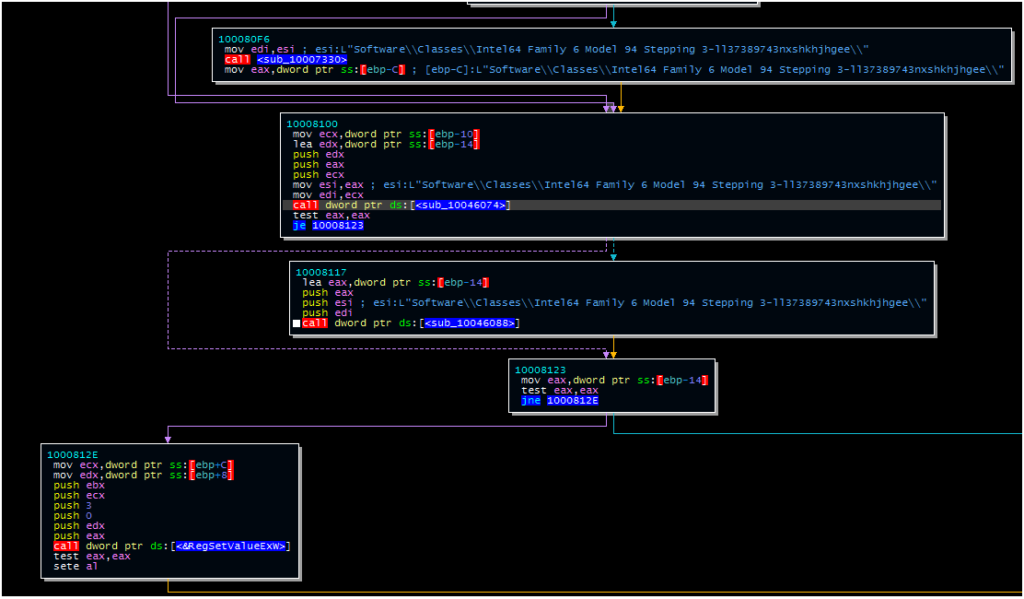

With sufficient privileges, the malware will create a new service named plugin_hostvr874u5Pn pointing at the plugin_host.exe executable with a start type of “2” (autoload):

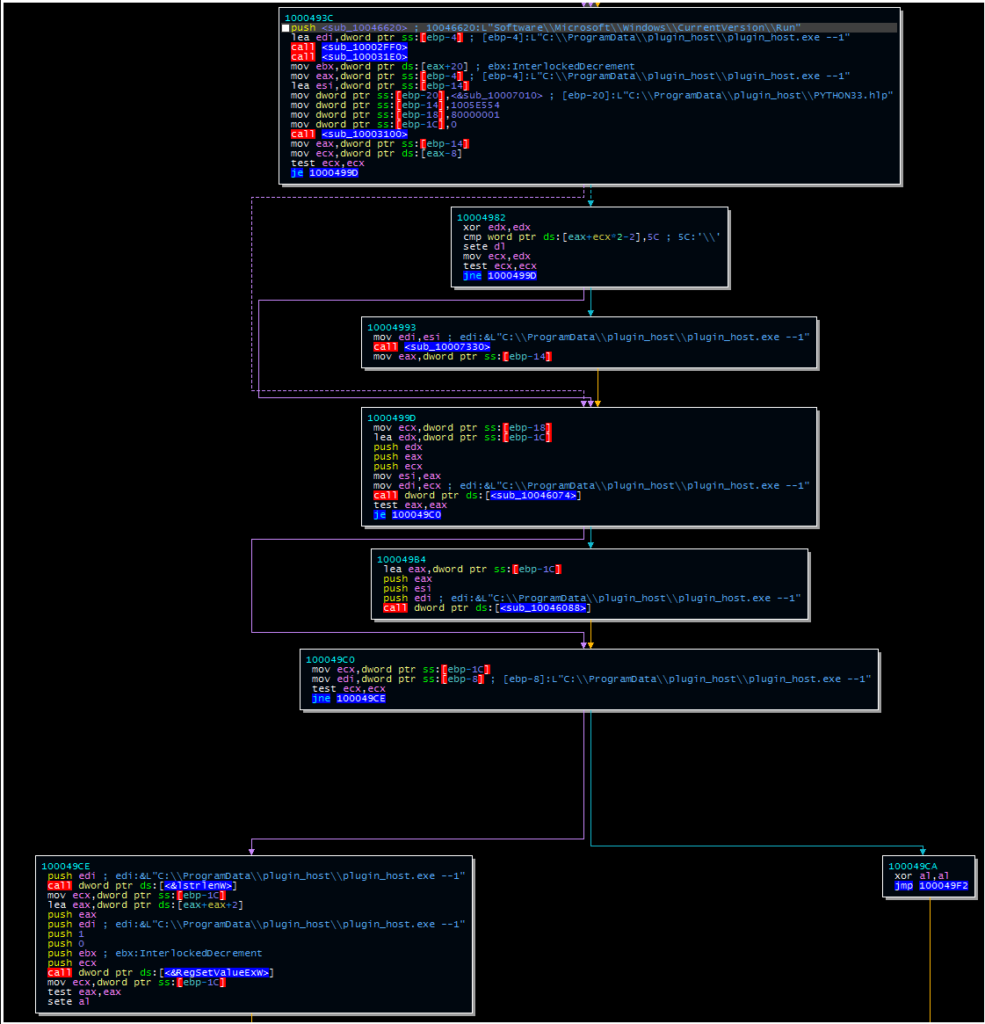

Otherwise, the malware will create a registry entry under the HKCU CurrentVersion\Run key named plugin_hostvr874u5Pn pointing to plugin_host.exe with a parameter of –1. The function then returns and the injection and core routines are executed.

Case 3

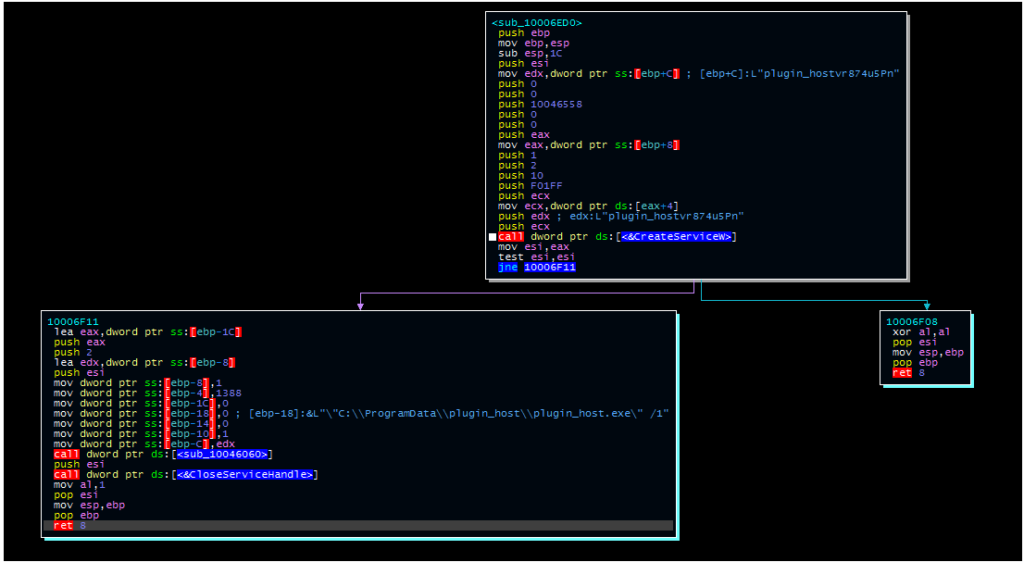

Case 3 contains a single function, referenced above and by NCC Group’s writeup on an earlier version of this malware as the “core functionality” routine. This routine contains the code used for process injection, but more importantly is used to:

– Write encrypted configuration values to the Windows Registry

– Perform a workflow for C2 communication

missary panda unit42

The workflow for this is shown below, and tracks closely with the previous NCC group reporting:

Following this, the malware enters its C2 routine. The malware uses the PolarSSL library to do this, and communicates with 138.68.154[.]133:443.

Concluding Thoughts

Having looked at each of the cases within the malware, we can compare this sample to the previously reported one, even though that file was never provided.

– The previous reporting described self-termination and WMI execution for Case 0. The WMI functionality appears to have moved to Case 1, and Case 0 now supports process injection.

– Case 1 now supports moving the files to the appropriate locations if they are not present, executing these files via WMI, or performing process injection. Previously, the file moving routines were in Case 0.

– Case 2 appears to be largely unchanged.

– Case 3 appears to be largely unchanged.

– There is no “Case 4,” although the malware will treat any number of parameters greater than 3 as a signal to head to the “default case.”

– The referenced debugging strings do not appear in this sample.

NCC group previously assessed that the malware might be undergoing active development. Given these findings from a sample a year later, it appears that was the case. There are minor upgrades, cases rearranged, and possibly one case removed. Still, based on the higher-level descriptions in that report and how closely they track with this more granular analysis, it would appear that this is the same malware family (with modifications).