When I first started this blog post, I had written what I felt was a more compelling introduction that implied that it was unethical to convert the largely public sector weather service into a completely private sector one. This was in response to the severe staff and resource reductions at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Weather Service (NWS) that NOAA oversees. Then, of course, this weekend happened.

At the time of this writing, there are over three dozen reported fatalities following a large series of storms and tornadoes that affected multiple southern and midwestern states including Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Alabama and Mississippi. Pictures of the destruction are available on Twitter, as are discussions from the time of forecasting through the time of the storms’ departure towards the East Coast.

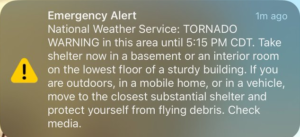

The aforementioned cuts to NOAA and NWS serve as a backdrop to all of this. These cuts create a very real problem for those who live in high-risk regions. The alerts that we use to notify people of severe whether events – and the underlying data, research, and forecasts that generates them – come from these organizations. The end products are alerts that are available online and are also often sent to your phone, and the private sector directly integrates these alerts into their own offerings.

The thinking behind these cuts is that private sector companies can and should replace the majority of the functions that the NWS and its parent NOAA perform – a way of thinking that is, quite frankly, naïve and that I am writing this post to challenge.

Here are my two main points:

- You should not assume that the private sector will provide you with a “better” product simply because of competition and the incentive to make money.

- NOAA and NWS provide a life-saving service, and this life-saving service is something everyone should have access to with no limitations.

Motivations for the Cuts

I recognize that citing Project 2025 is inherently political, but the arguments and objectives presented in this document are nearly identical to the arguments you’ll see in the public discourse, either from politicians or from commenters in the news and on social media. Project 2025 specifically notes a desire to:

- Have NOAA “dismantled” and its components eliminated, distributed, or privatized. (p. 664)

- “Focus the NWS on Commercial Operations,” as “the forecasts and warnings provided by… private companies are more reliable than those provided by the NWS.” (p. 675)

- Provide NOAA’s functions “commercially, likely at a lower cost and higher quality.” (p. 675)

- Downsize the Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR), as it is the “source of much of NOAA’s climate alarmism.” (p. 676)

Whether these are a direct driving force or an indirect force behind the cuts, I could not say. What they do show, however, is a written representation of a way of thinking that drives the actions being undertaken. When someone says, “This is what we want to do,” and then those things start to happen, it’s worth taking seriously.

With that document’s stated objectives in mind, let’s start with this weekend and evaluate weather the private sector is providing a “better” service when lives are at stake.

Private Sector Pitfalls

Private sector companies – particularly publicly traded ones – are really only incentivized to do one thing: make money. There’s some nuance to this in that “making money” really means “providing a return for investors,” but at the end of the day profit and revenue drive behavior.

The storms this weekend had already started to hit the affected states by the time Saturday morning rolled around, and I had been keeping tabs the night before. With this blog post in mind, I was curious how The Weather Company’s website would appear to a user querying the website for the weather in an area at risk.

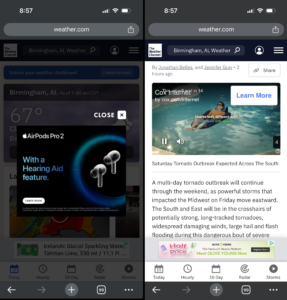

My first stop was Birmingham; while an official tornado watch for the area would not be issued until a few hours later, NOAA’s Storm Prediction Center had put out a warning detailing a “high risk of severe weather.” If you knew where to click, you could find an article about this on TWC’s website, but only after being served a full-screen advertisement for Apple’s latest Air Pods. Of course, the top-line inside of the article was not the possible tornado outbreak in the area. That got second billing to Cox Internet’s 15-second advertisement set to auto-play.

Scrolling down on the actual forecast page, you were presented with several more “articles” that included topics such as “Is it actually safe to land a plane on the snow?,” how to “protect your pipes from a frozen disaster,” and “ 4 dangers of heavy, wet snow.” These topics are no doubt of paramount importance to someone browsing the weather for Birmingham, Alabama in March.

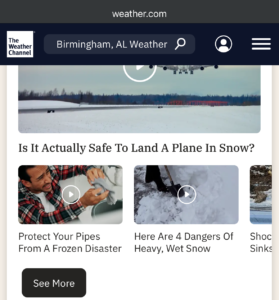

The most glaring issue on this page, though, was the inclusion of an “Activities Forecast” for the day. While TWC deserves some credit for advising that going camping might be a poor choice, running, hiking, and golf were all in the green.

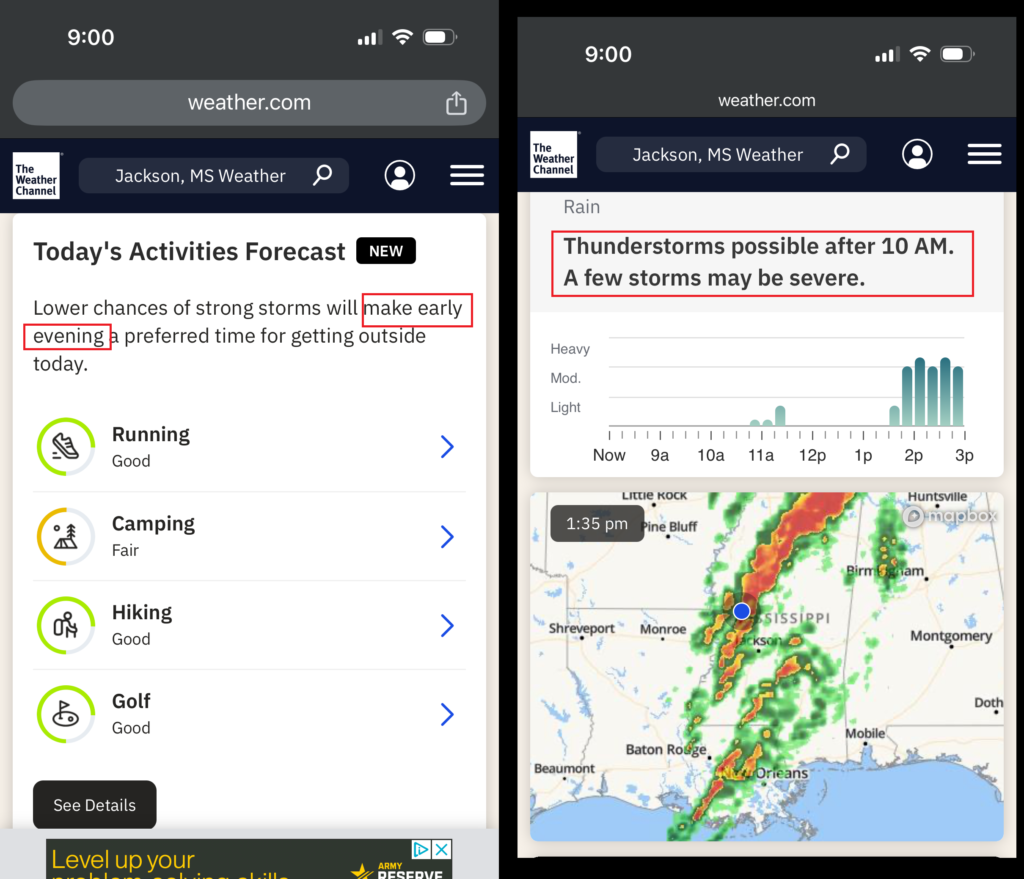

Jackson, Mississippi had a similar issue, with seemingly conflicting messages – green for running, hiking, and golf and a suggestion that “early evening” would be best for these activities, while also displaying a radar showing a particularly brutal series of storms “after 10 a.m.” and well into at least the afternoon.

To TWC’s credit, this activity tracker does appear to go away when it imports NOAA and NWS alerts, but by the time that happened, these storms were well on their way.

Everything I have described here is a safety issue in one way or another, and everything is driven by a private sector need to either raise revenue (through advertisements) or differentiate the product (through offering features like the borderline ridiculous “Activities Forecast”).

If you privatize weather services, this is always a risk, and you have no public sector safety net to operate as a check.

Private Sector Predictions

NOAA

In light of these events, it almost seems silly to have a discussion about weather predictions as I had originally intended. Still, most people on most days are checking the weather to find out two simple things: the temperature and if it will rain.

Weather predictions have improved substantially over the past few decades. Nate Silver wrote about this in his book in 2012 and the trend has continued in the years since. As Silver noted in his book, two factors are at the heart of this trend: improved collection methods and improved computational power.

NOAA operates over 1000 buoys in the ocean, owns and operates eight satellites, and operates an additional seven satellites in support of these objectives. NOAA owns or leases multiple buildings and research facilities that process this and other data and generate predictions for NWS. Dozens of these facilities are now at risk, with the White House’s comment to the New York Times on the matter being simply that they “do not respond to reporters with pronouns in their bios.”

That’s a very brief summary of what NOAA and NWS provide. How does the private sector fare with that information? The answer is mixed, hitting the mark in temperature but with one glaring historical problem when it comes to predicting precipitation that I will discuss in a moment.

For studies and discussions, I’d point readers to two: the first is from Cliff Mass, who has advocated for more computing power to go towards NWS and NOAA and who has also pointed out operational areas in which NWS and NOAA have fallen behind. Cliff has also opined that there probably are some redundancies in NOAA based on his own experience working with them, but has argued that the current staff cuts are a mistake.

He also cites a second source, ForecastAdvisor, which compares the results of weather predictions across different sources and which shows NWS and NOAA coming in fourth or worse in most areas. It’s worth looking at – I think it hits the mark on temperature, but may not comprehensively study precipitation (the methodology is a little opaque).

Precipitation

This brings us to the biggest problem. As Nate Silver discusses in his book and others have researched in the past, weather forecasts from private organizations are incentivized to make money and this is not necessarily the correlated with being accurate. This is most notable when it comes to the issue of precipitation: people want to know if it is going to rain or not. If you tell people that it will rain and it doesn’t, they will be less upset than telling people it won’t rain and it does.

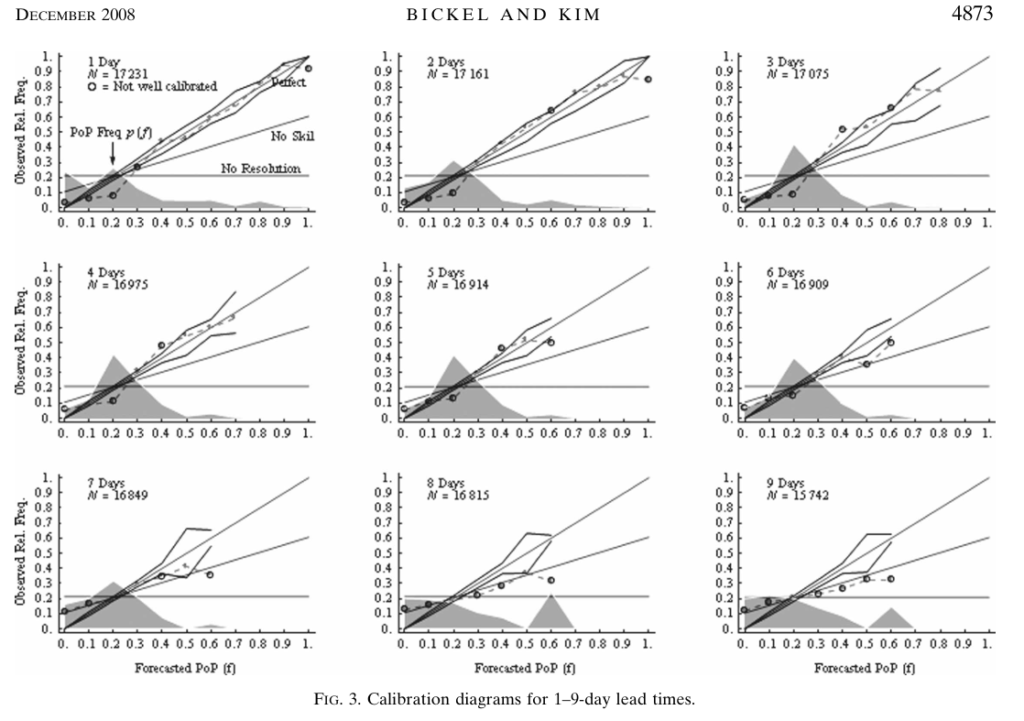

This has manifested itself in something referred to as a “wet bias,” in which forecasters from private companies intentionally overstate the probability that it will rain. They also often avoid offering 50/50 percentages. You can see this data in a 2008 study available for free that examined The Weather Channel’s propensity to do this. The study is fairly technical, but page 7 has some pretty digestible graphs showing the problem.

To put it in plain English: the private sector has historically demonstrated a willingness to deliberately provide a less than accurate forecast, with a former vice president of The Weather Channel (before it was The Weather Company) openly admitting that if they didn’t, they would “probably be in trouble.” This is a problem, given that forecasts (along with warnings and alerts) are used to make critical decisions for businesses, activities, and entire communities.

I have not come across a more contemporary study, but so long as weather is tied to a commercial incentive, this risk remains.

Additional Thoughts

Though this is not the subject matter that I usually write about – North Korea and Iran will have to wait for another time, I suppose – this is not so different from my other posts in that this probably represents (at most) about a third of what I could write.

In addition to NWS, NOAA has several other line offices, including the Marine and Aviation Operations (OMAO), Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), National Ocean Service (NOS), Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR), and National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Services (NESDIS). One could almost certainly write a post about the work that each of those organizations do, and why each of those offices can’t just be blindly reduced without significant consequences.

So here is what I will say: Weather is inherently tied to public safety and the public interest. If you received an alert this weekend (or any weekend), it came from NOAA and the NWS. I’ve personally received them before and made decisions from them, ranging from “I should wait an hour to drive home” to a more recent “I need to go into my basement because there is a tornado warning.” These are not things people should have to pay for or be bombarded with advertisements to receive.

I’ll close with this: the people driving these changes have it backwards (and they probably know it). We should be putting more into NOAA and its offices, and not less.